The Battle of Algiers

1966/DVD 2004

Director: Gillo Pontecorvo

Cast: Saadi Yacef, Brahim Hadjadj, Jean Martin

Reviewed by Nancy Keefe Rhodes

If you’ve happened to hear that as a young man the Italian filmmaker Gillo Pontecorvo was inspired to forsake photojournalism and take up making movies by watching a single decisive film, and you’re lucky enough to find a copy of Roberto Rossellini’s 1946 Paisá, you will see from the very opening scene what attracted the sensibility of one who also studied composing, grew up under Mussolini, led an anti-Fascist resistance in the city of Milan during World War II and went on to make the legendary cinema vérité-like epic of Algeria’s independence, The Battle of Algiers (1966). I was lucky enough to borrow a personal VHS copy of the European release version, with the English-language dialogue of American GIs and British troops subtitled in Italian, and right there – in the opening scene, where the Yanks are advancing through the narrow, twisting stone alleys of Sicily at night, rifles at the ready, and then up to a ruined seaside fortress in the moonlight, in the first leg of the liberation of Italy – you can see a cinematic vision that fed Pontecorvo’s filming of the running battle through the twisted streets and over the rooftops of the Arab quarter – the Casbah – in Algiers.

Paisá is – criminally – not available on US format DVD right now. An anthology of six episodes set in different parts of Italy from 1943-45, it chronicles the Allied liberation of Fascist Italy from the perspective of ordinary people who interacted with, primarily, US GIs, often turning on misunderstandings due to language and O’Henry-like twists. Paisá also exposed Pontecorvo to the long tracking action shots that provide a deep visual pleasure that today’s jump cutting can’t approach, and to unashamedly moving music as backdrop. A good deal of the emotional heft of The Battle of Algiers, for example, comes – one realizes afterward – from the fact that Ennio Morricone’s score gives the same dirge-like music to Arab and European deaths alike, all equally tragic and wasteful.

There is also a strange shock of recognition in Rossellini’s film, which curiously the subtitles seem to spark first. We’re not used to English speech translated into another language in the text crawling under the action. It seems backwards somehow, snags your attention. But here is a film with American characters that an outsider made and he got us right. This is one of Paisá’s many exhilarating pleasures and, as significant, one cause of an accumulating deep trust in the director’s vision. While it’s harder to track than a particular visual approach, this capacity to portray those who are different so that they recognize themselves – and experience themselves as truly seen by an outsider – may be the more important lesson that Pontecorvo took from Rossellini.

This is worth mentioning at some length because Pontecorvo’s Battle of Algiers has been so decisively influential among filmmakers working today. The Criterion’s 2004 DVD set – unusual with a highly expansive three discs – includes interviews with Spike lee, Julian Schnabel, Steven Soderbergh, Oliver Stone and Mira Nair. The Indian director says Battle of Algiers is “the one film in the world that I wish I had directed.” So how these two Italian directors perceived and filmed war and liberation has come to gradually permeate what’s on our screens. What is further remarkable is how little the course of war and its political justifications have changed.

The Battle of Algiers covers the years 1954-57, culminating in the title’s battle, and largely following the conversion to politics and rise to leadership of a young street thug, Ali La Pointe (Brahim Hadjadj), after he witnesses from his cell what was actually a pivotal execution by guillotine of two Algerians in the prison’s courtyard. Most of the Algerian characters in Battle portray actual historical figures – some such as Ali named literally – and all nonprofessional actors. Saadi Yacef, who sought Pontecorvo to propose making Battle, plays a character in the film named Jaffar who is essentially modeled on himself. The French paratrooper commander, Col. Mathieu, is a composite of French commanders played by the French film actor Jean Martin. Dramatically, soon after the film opens we see Ali La Pointe trapped behind a building’s wall in a hide-out, ordered to come out by waiting French troops. Ali La Pointe did not come out. The resulting explosion entombed him and his little band. Three years after the end of this war, Pontecorvo rebuilt the house where Ali died and blew it up again for the film.

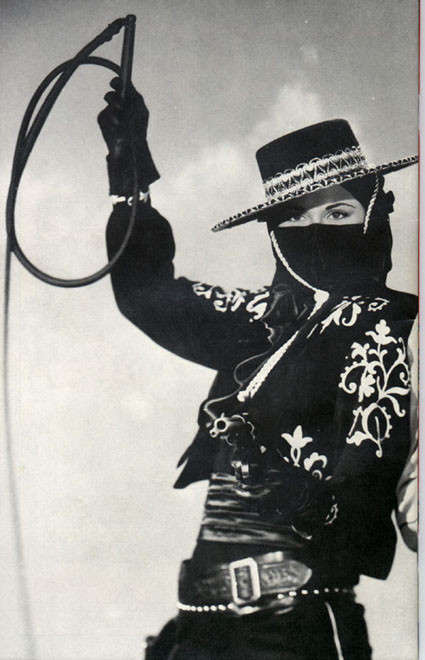

The Battle of Algiers is structured as a flashback from this moment in 1957, when fresh French paratroopers had arrived, surge-like, in response to escalating attacks against police and troops and – a new tactic – three women had planted bombs that detonated in public gathering places frequented by Europeans. Pontecorvo was especially intent to portray the role of women in Algerian independence; the powerful montage in which they prepare for and carry out the three public bombings occurs without dialogue and backed by the Algerian anthem, “Baba Salem.” French troops, whose use of torture in interrogation has of course compared to more recent controversies, then arrived to break a looming national strike called by the National Liberation Front (FLN) that was timed to coincide with United Nations debate on Algerian independence.

Criterion outdoes itself with this set’s bonus features, which more than repay the several evenings you’ll spend watching them and which will leave you angry at what you didn’t learn in school, and aghast at how old the argument is that terrorism justifies torture. These include a string of interviews with surviving French officers and nationals – the colonel who headed the death and torture squad, the French officer (a decorated hero in French Indochina) who resigned and exposed atrocities, the French-born newspaper editor who was himself tortured for siding with the Algerians – as well as recent interviews with Saadi Yacef and Zohra Drif-Bitat (one of the three women bombers), both of whom sat in the Algerian parliament at the time of this DVD release. There’s a short 1989 documentary that Pontecorvo made upon revisiting Algeria, a documentary about his film career narrated by Edward Said, and a conversation among ABC News’ Chris Isham, former national security coordinator Richard Clarke and the State Department’s counterterrorism coordinator Michael Sheehan, filmed in May 2004.

But first watch the movie itself.

*******

This review appeared in the 1/17/08 issue of the Syracuse City Eagle weekly, where “Make it Snappy” is a weekly column reviewing DVDs of recent movies that did not open theatrically in CNY & older films of enduring worth.

AGORA: Dragged from her chariot by a mob of fanatical vigilante Christian monks, the revered astronomer was stripped naked, skinned to her bones with sharp oyster shells, stoned and burned alive as possibly the first executed witch in history. A kind of purge that was apparently big business back then.

.jpg)

CRITICAL WOMEN HEADLINES

2/24/08

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment