Resisting Paradise

2003

Director: Barbara Hammer

Cast: Marie-Ange Allibert Rodriguez, Marguerite Matisse, Henri Matisse

By Nancy Keefe Rhodes

It was a case of being in the right place at the right time. When filmmaker Barbara Hammer went to France in the spring of 1999 to Cassis, a few miles east of the port city of Marseilles, famous for its limestone cliffs and its wine, she intended to investigate the unique quality of light that had drawn painters to that region. For example, the painter Pierre Bonnard left Paris for good in 1910 for the southern coast, and Henri Matisse had moved south in 1917, settling near Nice. They carried on a lively correspondence into their later years – living until 1947 and 1954 respectively – about the light and landscape that so nurtured their palettes, and both refused to budge during the Nazi occupation of France in World War II. We have all probably seen light a little differently since the Impressionists, whether we realize it or not. And for Hammer, this project would be a natural investigation. A painter once herself, she’s engaged in experiments with light, editing, format, film emulsions, and approaches to subject matter in 80-some videos and films over the last four decades. She even notes Matisse’s remark that cinema “has advantages” over painting.

Once there, Hammer discovered others had moved through Cassis and the southern coast during World War II besides painters hunting perfect light – refugees fleeing the Nazis, and resisters, both in the thousands. While Matisse painted, his estranged wife Amélie, his son Jean and his daughter Marguerite were part of the French Resistance. The Gestapo caught and tortured Marguerite, who drove to Paris three times a week with messages, and shipped her to Ravensbrück concentration camp.

As Hammer uncovered an aging network of survivors from those years – Lisa Fittko took Jewish refugees on foot through the Pyrenees Mountains into Spain, Marie-Ange Allibert Rodriguez supplied identity papers and food stamps from her City Hall office – another convergence de-railed her film plans.

In March 1999, NATO began bombing the break-away Serbian province of Kosovo, intending to drive out the Serbian police and paramilitaries engaged in atrocities against the majority Albanian population, the latest convulsion in the break-up of the former Yugoslavia that had stretched across the 1990s.

Every night in Cassis, Hammer says, she watched Kosovar refugees on French TV as they fled “ethnic cleansing.” When they streamed home again in June, revenge killings against the Serbs started, even as the UN tried to organize elections. So the film that Hammer finished in 2003 – and is bringing to Syracuse next week for two guest screenings – is not what she set out to make. Instead she decided to investigate these questions: What are our responsibilities during war? How can art exist during political crisis?

Convincingly gorgeous, Resisting Paradise captures what could so visually intoxicate Bonnard that he could “drown” in the landscape there. Hammer’s capacity to recreate this on-screen endows her questions with a power that carries this film well past the standard educational documentary. To address those questions, she creates a kind of dialogue between the painters, with snatches read from their correspondence, and “ordinary people,” made up of re-enactments, readings and voice-overs, archival footage, new interviews and footage that imagines the transformation of what’s seen to what’s painted.

The comparison is unsettling and challenging. Matisse writes to Bonnard that “a little painting no bigger than your hand sold for 100,000 francs – this is a golden age for artists!” His grandson follows, describing his mother’s torture (and it sounds like water-boarding to me). Lisa Fittko describes the seemingly failed escape and suicide by morphine tablets of philosopher Walter Benjamin, whom she guided to Spain’s border, where the Spanish police stopped his party and held them overnight in order to send them back. Forger of identity papers and food stamps Marie-Ange Rodriguez, who says she is “87 ½” and in fact died shortly after Hammer’s interview, recalls, “I was never afraid. Everyone knew and no one betrayed me, never, even those on the side of the Germans.”

That comparison also made some artists at Harvard, to whom she showed the film while it was still a work in progress, feel “attacked.” In order to soften Matisse, she added more footage of his grandchildren. Though Jacqueline Matisse Monnier and Claude Duthuit provide the details of their mother’s and grandmother’s treatment at the hands of the Gestapo, they also insist that Matisse – given his health – could do nothing other than he did.

Now we can hardly miss more synchronicity in Hammer’s bringing this film to Syracuse at this point. After years under UN administration, Kosovo finally declared independence on February 17th. Within days, 150, 000 Serbs protested in their capital’s streets, burned and looted foreign shops, and fire-bombed embassies of nations supporting Kosovo (ours included).

Hammer hasn’t been to Kosovo, but last May she was in Serbia, Croatia and Montenegro, where traveling in a car with Serbian plates meant hurled eggs and angry shouts. Speaking by phone on Monday from Woodstock, where she lives when not in Manhattan, Hammer said these events of recent weeks “really bring this full circle and may lead to a situation similar to 1999.”

Hammer visits Onondaga Community College in Syracuse on March 6th as the guest of the Reel World documentary series, part of Art Across Campus. Reel World brings indie documentaries with limited release to campus with screenings that welcome the wider community; this year’s Art Across Campus explores how artistic expression documents wartime experience. Faculty organizer Linda Herbert says Hammer’s vast body of work – experimental documentaries and queer cinema landmarks like Nitrate Kisses (1992) – and the start of Women’s History Month all make this “a perfect fit.”

Renting Hammer’s films is hard – netflix.com only offers History Lessons (2000), the third in her trilogy of experimental documentaries about lesbian and gay history (besides Nitrate Kisses, 1995’s Tender Fictions) – but Women Make Movies carries her earlier films, some are for sale on her website (barbarahammerfilms.com), and she’s considering other commercial DVD distribution. She’s also represented in the landmark WACK! international exhibition of 1970’s Feminist art, on view now until May at the Museum of Modern Art’s PS1 Contemporary Art Center in New York, where she’ll speak on a panel of experimental filmmakers this Saturday.

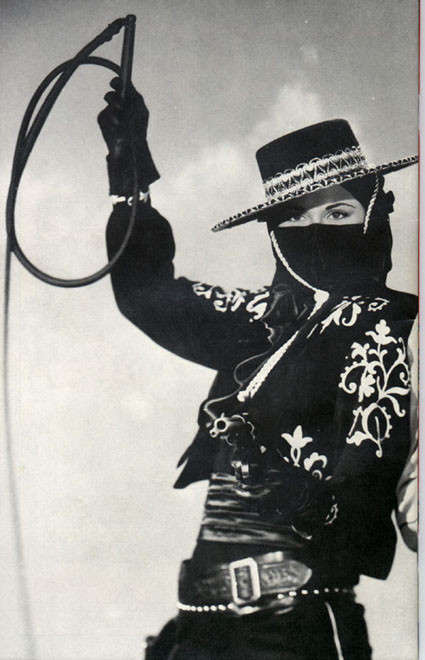

Hammer has also just finished two films about the dying tradition of women deep-sea divers of the matriarchal Korean island of Jen-Ju Do. Like Resisting Paradise itself and My Babushka (2001), which documents her search for her Ukrainian roots, the two Jen-Ju Do films address concerns ranging wider than queer history. On Monday Hammer commented that Lover Other, her 2006 film about two women who were both artists and lovers and resisted the Nazi occupation of the island of Jersey during World War II, is “really a coda” to Resisting Paradise, which had no lesbian or gay figures in it. “I went as far as I could go with lesbian history,” Hammer says. “I’m also an artist, a resister myself.”

A shorter version of this review appears in the 2/28/08 issue of the Syracuse City Eagle weekly, where “Make it Snappy” is a regular column reviewing DVDs of recent movies that did not open theatrically in CNY & older films of enduring worth.

AGORA: Dragged from her chariot by a mob of fanatical vigilante Christian monks, the revered astronomer was stripped naked, skinned to her bones with sharp oyster shells, stoned and burned alive as possibly the first executed witch in history. A kind of purge that was apparently big business back then.

.jpg)

CRITICAL WOMEN HEADLINES

2/29/08

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment