GENDER CRASH

By Sikivu Hutchinson

Blackfemlens.org

While mainstream critics continue to foam at the mouth over the “verisimilitude” of Academy winner Crash’s racial politics, the film’s retrograde gender politics have been all but ignored. Crash’s testosterone-soaked L.A. is a parable of male redemption forged on the backs of women. By using the picture of a grief stricken black woman cowering in the arms of a white male policeman as the signature image for its newspaper ads, the subtext of Crash’s “provocative” charge rests in its exploitation of the political and social disenfranchisement of women of color. The film’s centerpiece act of racial profiling hinges on the sexual violation of an African American woman (played by Thandie Newton) who then becomes a pawn in the movie’s male redemption sweepstakes. After Newton’s character is molested by Matt Dillon’s racist thug cop at a traffic stop, her plight is effectively eclipsed by her buppie husband’s inner struggle with his sense of alienation and emasculation as a white-identified black man. The age-old dance between white men and black men for patriarchal control is hence waged over the body of a black woman—while the thug policeman gets to redeem and regain his sense of moral authority by rescuing the hapless black woman, the black producer legitimizes his manhood through a deadly verbal duel with the LAPD in a gratuitous attempt to show how “hard” he really is.

The display of black male “hardness” for the validating gaze of white male authority, set against the “backdrop” of the black woman’s body, is an all too familiar historical “mise-èn-scene.” A cornerstone of the antebellum plantation economy, degraded black female sexuality has not only become one of the most valuable commodities in pop culture but in the media’s eroticized fantasy of urban criminality. The assault of Newton’s upper crust buppie black woman is a not so subtle reminder that black women who aspire to the trappings of domesticated protected white middle class femininity are liable to be treated like just another “ghetto ho.” Yet the film’s retrograde images of passive Asian and Latina femininity also fit squarely into this paradigm of female serviceability and patriarchal control. In Crash’s universe, a female El Salvadoran police detective beds her African American partner and becomes the ballast for his professional and personal travails, while her dilemma of being one of the few Latinas on a notoriously racist sexist police force goes unexplored: a “generic” Latina maid is strategically deployed to validate the bruised ego and self-pity of a racist rich white woman: and the wife of a Chinese smuggler is depicted as a shrill harpy who spews broken English at the scene of a fender bender she’s been involved in. This trio of portrayals bespeaks an L.A. in which women of color have zero political agency of their own. In this respect, the film’s lack of fully-realized female characters is not only a reflection of the overall bankruptcy of Hollywood gender representation but is yet another example of the assassination of the image of women of color in mainstream American society.

The egregiousness of these portrayals is particularly pronounced with regard to the film’s Asian characters. Both the Chinese female character and her husband provide “comic relief” for the voyeurism of non-Asian audiences who have been trained to view all Asians as de facto fresh off the boat others. Their narrative is tacked onto the movie as a coda with a twist that not only emphasizes the mendacity of the immigrant smuggling underworld but implicitly highlights how “out of tune” these old world figures are with core “American” values of freedom and democracy.

After he is hit by a pair of black male carjackers while standing at the door of his van, the Chinese male character is next shown much later in the film recovering from his injuries in a hospital as he is fawned over by his wife. Other than a reunion scene at the hospital, these characters’ screen time is flat and stereotypical. The lack of nuance given to the portrayal of the smuggler, coupled with the shrill incomprehensibility of his wife, effectively dehumanizes the two characters.

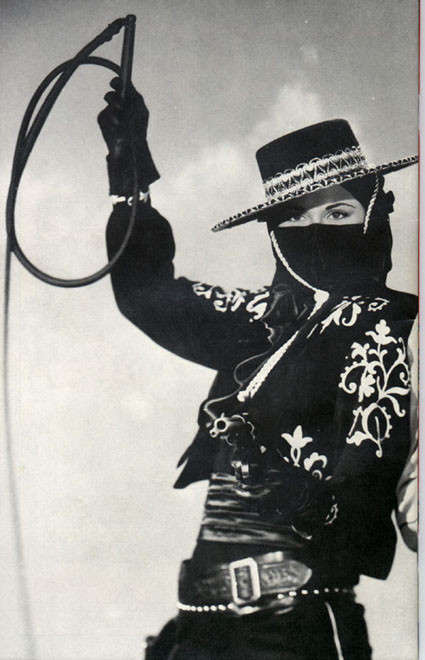

The “feminization” of Asians in general and Asian men in particular is a common thread in Western film and literature. Time and time again Asian men are vilified as inscrutable scheming purveyors of hierarchical backward cultures that are incompatible with Western modernity, while Asian women are stereotyped as coy lotus blossoms or sneaky dragon ladies who exist solely to reinforce the heroism and moral superiority of white male protagonists. In one of the most dubious images of the film, a woman who has just been “liberated” by the black male character who discovers her and the other smuggled immigrants in the back of the Chinese male character’s van gazes amazedly at the display of flashy goods in an electronic store. Shot in the dreary night of an amorphous Los Angeles, the paradoxical implication of this scene is that whatever the barbarous circumstances that brought her to the U.S., this is the land of freedom, democracy, and capitalist plenty and anything is possible if you bootstrap. Swallowed up into the maelstrom of the big bad city, she becomes yet another faceless voiceless prop in the film’s ethnic arsenal. The larger truth of how women like her have come to comprise the backbone of L.A.’s underground economy is a narrative to powerful for the film’s pat moral of phony redemption.

HIGH ANXIETY CRASH COURSE ALONG THE COUNTRY'S RACE AND CLASS DIVIDE

By Prairie Miller

Set logically in LA, the road rage capital of the world, Crash weighs in on the explosive mix of cars and race that notoriously tends to play out there. Paul Haggis, who just struck it rich with his screenplay for Million Dollar Baby, moves on from Baby's skid row for his directing debut in a movie that weaves in and out of the harrowing and yet often deeply touching high anxiety network along the California race and class divide.

One of the dirty little secrets of the car-dominated modern US city and the way they've been shaped (and yes, the suburbs too), is that they've been built to please the automotive and oil industries, and not to create people-friendly, close-knit communities with the emphasis on human proximity and connectedness. If LA served as the shining example of this dubious model, it has also been the nerve center of its fateful shortcomings. That would be everything from smog to profound alienation.

And Haggis, unlike the typical filmmaker who sees no value in connecting to the larger world around him, let alone history, creates raw, candid and bracing drama out of all the unspoken race and class tensions that surround and on occasion intrude into our waking lives. This is by no means a simple task, and Haggis is sometimes lured into the pitfalls of emotional excess and contrived coincidences.

Latching on to the current popularity of inverted narrative, where a connection among the characters is revealed later rather than sooner, Haggis builds his story with a measured and haunting pace. Spontaneous racial hostility and fear break out around a series of car crashes. A pair of young ghetto carjackers cause otherwise upstanding elites, like the wealthy housewife played by Sandra Bullock, to morph into perpetrators of foul racism, as against the Latino locksmith securing the newly paranoid woman's front door. Matt Dillon, a cop who is stressed out by a medical bureaucracy that isn't properly caring for his ailing father, irrationally retaliates by hurling mean spirited racial epithets over the phone to a Black medical office worker, and later on further works off his resentments by molesting an affluent Black female motorist (Thandie Newton) under the pretext of frisking her.

These are just some examples of a film teeming with solemn recognition of the nasty complexities of living in a multicultural society, and much of what remains unspoken racially in America being neatly shoved under a complacent rug. But far from just a self-critical expose, Crash is also a search for goodness even in the darkest heart in the real world we live in. And potential redemption that is in no way the easy happy ending, but tentatively seeks to lead in that enormously difficult direction.

Prairie Miller

AGORA: Dragged from her chariot by a mob of fanatical vigilante Christian monks, the revered astronomer was stripped naked, skinned to her bones with sharp oyster shells, stoned and burned alive as possibly the first executed witch in history. A kind of purge that was apparently big business back then.

.jpg)

CRITICAL WOMEN HEADLINES

10/25/07

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment